When I was a kid, my brother, Steve, and I didn’t always get along. Actually, I was often downright mean to him, as I wrote recently in this travel story for Afar magazine:

When I was a kid, my brother, Steve, and I didn’t always get along. Actually, I was often downright mean to him, as I wrote recently in this travel story for Afar magazine:

“Can we put Stevie in the trash now?” was how it began, when I was almost 4, a week after my newborn brother came home from the hospital. Things got worse from there. At first, I merely took advantage of his little-brother devotion, bossing him around to find Lego pieces for me to build with, but then I turned mean. At our grandmother’s house, I sneezed on him, intentionally. I boasted I could make him cry in three words or less. Once, when we were out skateboarding with my friends, I poured orange soda over his head. I’d like to say it was to impress my pals, who were mostly jerks. But clearly, I was, too.

Over the course of the story, which details our bonding trip to frosty Montreal, Steve and I managed to find new ways to get along. Or really, I figured out new ways to deal with him, despite the fact that I was wracked with guilt about what I’d put him through decades earlier.

This is kind of normal, I think. Over at the BBC, Anthony McGowan has a wonderful essay about, I guess, morality. Are you, he asks, a hero or a villain?

There is, of course, an almost irresistible human impulse to look on ourselves as the goodies or – with a little more grandiosity – as the heroes of our own narratives, whether we’re fighting over the height of our neighbour’s leylandii hedge or authorising air strikes on crumbling dictatorships.

I strongly suspect that all of the monsters of history, from Attila to Saddam, by way of Stalin, Hitler, Mao and Pol Pot, have viewed their actions as in some way ethical, conforming to a moral code, be it religious, tribal, Nationalistic or ideological.

And the lesson of this is that it’s always worth interrogating our motives and that, in fact, our interrogation should be most rigorous when we are most convinced of the purity, honour and goodness of our intentions.

This is great stuff, the kind of thing that needs to be said over and over again. Actions and behavior look different from different points of view. And McGowan, too, uses an incident from his childhood to illustrate his point. The short version: His group of friends, led by a kid named Chris, allows a sad sack named Duffy to hang out with them, takes him to a fetid stream (“the beck,” they call it), and then…

“There’s a cool place to jump. Up at the pool. You have to steppy-stone on the fridge. It’s not hard – I’ve done it. Chris’ll think it’s cool.” He looked up at me. “OK.”

“Duffy’s jumping the fridge,” I screamed at the others, leaving him no time to change his mind. Duffy took off his blazer and gave it to me. Chris was telling him what to do. Duffy now smiling, nodding. He looked happy for the first time since his mother had kissed him two years before.

Duffy prepared himself, he ran, he jumped. I couldn’t see his face, but I could imagine it. And I have imagined it, many times. He’d left it all in his wake, the years of horror, the beatings, the dog mess smeared on his blazer – all that. He was a butterfly shuffling off the dry, brown cocoon, becoming beautiful.

And then Duffy’s foot came down on the fridge and the fridge, as it was meant to do, betrayed him. Into the water he fell, his face contorted with surprise and fear. Of course everyone found this hysterical. Laughter, shouts, jeering.

Clearly, McGowan, like me, has been haunted by his actions, and perhaps rightly so. He was a dick to Duffy. But as I read his words, I couldn’t help thinking this was the wrong story to tell. After all, he was just a kid, and the point of being a kid is that we sometimes—okay, often—okay, most of the time—make poor decisions. We succumb to peer pressure, we lie, we tend toward laziness simply because we can, and because we know that adults have to be responsible for us. And yes, sometimes we treat other kids like absolute shit. And sometimes we get treated like shit as well. It’s possible to occupy both positions. I know—that was me. Abused and abusers, whether the abuse if casual or prosecutable, exist on a continuous spectrum. And it’s when we’re adults who should know better that true guilt comes into play. I would’ve liked to read an account of a mistake McGowan made as a grown-up—that might be even more powerful.

And besides, as Elizabeth Weingarten wrote the other day in Slate, sometimes our perceived crimes have little effect. Weingarten’s subject is Santa Claus, how he doesn’t exist, and how, as a third-grader, she intentionally revealed his non-existence to a Santa-believing friend:

“You know there is no Santa Claus, right?”

Instantly, my cheeks burned as I realized I had committed a grievous wrong. So great was my shame that it’s blocked out any memory of how, exactly, Jacqueline reacted. All I recall is wishing I could dissolve into metallic goo and seep away through a hole in the ground, a la Alex Mack. I shouldn’t have told her!

I’ve felt guilty about it ever since. Each year, around Christmas, I recall the events of that afternoon and wonder: Did my gaffe kill part of her hopeful, glittering soul? Does she think of me each year by the Christmas tree, her eggnog made bitter by the memory of the day I took an ax to her childish sense of awe and wonder?

The answer, she learns, is no. Weingarten tracks down the old friend, who it turns out has “zero recollection” of the incident. It simply hadn’t fazed her at all, and she in fact remembers much more strongly learning of Santa’s non-existence from another friend.

So it goes, in a slightly different way, with McGowan’s Duffy, who manages to grow up all right anyway and joins the Army, apparently with some success. Did McGowan’s childhood betrayal wreck Duffy’s life? We’ll never know for sure, but McGowan shouldn’t beat himself up over it, just as I’ve learned that my crimes against my brother were mostly forgotten as well. We were kids, and kids can be cruel. Growing up is learning to shed that cruelty, and we shouldn’t judge each other, or ourselves, until we’re older.

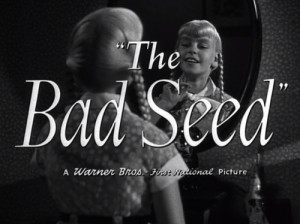

Unless, of course, you’re this kid: