I don’t pretend to understand what constitutes a discussion about social mores in England, but these days it apparently involves something called the Tatler, Martin Amis, and fairy godparents. That is, British godparents suck:

I don’t pretend to understand what constitutes a discussion about social mores in England, but these days it apparently involves something called the Tatler, Martin Amis, and fairy godparents. That is, British godparents suck:

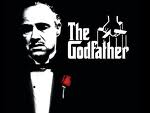

It’s what one might call the Godparent Trap: Like a horror B-movie, legions of zombie godparents are walking mindlessly among us. The parents who do the asking don’t know what they’re asking for. The friends who do the accepting don’t know what they’re accepting. And the children who do the receiving don’t know what they’re receiving.

I find this all kind of fascinating, partly because Jean and I put some real thought into who we chose as Sasha’s godparents. Or maybe that was just me—they don’t have such an institution in Taiwan. In any case, we/I picked two friends who both have very strong moral centers—who are definitely concerned with doing the right thing. One is religious (Catholic), the other is, as far as I know, not (Chinese). We don’t always agree with their points of view, but their points of view are instructive nonetheless.

Do I actually expect them to guide Sasha on a religious/moral level? Hardly. My own godparents didn’t do anything of the sort.

The way godparents affected my life was not morally but, perhaps, thematically. My godfather is my uncle—my dad’s brother—and my godmother was Marsha (Marcia?) Moss, a librarian in Concord, Massachusetts. It’s a hard thing to quantify, but simply knowing who these people were had something of an effect on my life. Okay, my thinking must have went as a child, my godmother is a librarian—what does that mean for me?

In other words, it probably doesn’t really matter what a godparent does. What matters is who the godparent is, and how a child sees their selection in light of his or her own development.

So, chill out, Brits, and go spend some time at your local library. I think you might even find Martin Amis there.