Perhaps it is unfair to pin this on Montessori schools. Because we had some of this in our daughter’s preschool, which was without discernible doctrine. And really, I’m happy enough with my boy’s school, beyond a vague wish that we could actually afford it. But still. There is a way of speaking that the Montessori teacher excels at, and it drives me slightly insane. Clinically speaking, it involves referring to me in the third person though I am standing right there in front of the teacher. A recent snippet while dropping the boy off:

“Good morning Nico”

“Hallo”

“You don’t have your naptime bag?”

“Umm, no.”

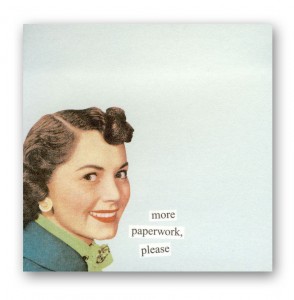

“Maybe your daddy forgot to bring it?”

silence (the boy might have been equally confused by her speaking to me through him–I am, after all, standing RIGHT THERE)

“Your daddy must have forgotten the bag this morning.”

“mm”

“It’s okay this time. But daddy should bring your naptime bag after each weekend…”

I was tempted at this point, of course, to say to my son something like “maybe the teacher doesn’t know that daddy is standing right fucking here.” As if the teacher and I were a divorced couple communicating through our children in that annoying way that divorced couples sometimes do.

Instead, I broke down the fourth wall and spoke directly to my interlocutor, who, to her credit, was also able to communicate that way just as well. She explained that the naptime bag with sheets and other things my boy might pee on are sent home on Fridays, and need to be brought back on Mondays. There, that wasn’t hard to say, was it?

It’s fine. A small thing, of course. But as with many small things in Montessori, I’m sure the teachers would defend the pedagogy behind it with their lives. If they talked directly to the parents, no doubt, it would simply diminish the poor child which yet again has to listen as adults converse above them. But if a child-centered conversation means two adults talking through a preschooler, then count me out. Or, rather, tell the teacher to count daddy out.