(This is our second run of “The Tantrum,” in which each of our four regulars will address one subject over the course of a week. Previous Tantrum: TV or not TV?)

Well, my opinion on this is pretty straightforward. My wife and I are devout believers in the concept of Ought—that is, you do many things not because they’re required but because you Ought to. And if your kid gets into something that genuinely risks injuring other people, there have two things you Ought to do: Get him to stop, and if you try absolutely everything and can’t, then call in the Feds. (As for relatively victimless crimes, I’m electing to punt till he’s a teenager.) I am confident enough in our parenting abilities that it won’t come to that, barring something entirely beyond parental control. And call me an egotist if you wish, but I do believe that my wife and I are able to make good enough choices to keep my kid from being the top-ranked Al Qaeda recruit of 2027. (I’d say he should try for Princeton first.)

Well, my opinion on this is pretty straightforward. My wife and I are devout believers in the concept of Ought—that is, you do many things not because they’re required but because you Ought to. And if your kid gets into something that genuinely risks injuring other people, there have two things you Ought to do: Get him to stop, and if you try absolutely everything and can’t, then call in the Feds. (As for relatively victimless crimes, I’m electing to punt till he’s a teenager.) I am confident enough in our parenting abilities that it won’t come to that, barring something entirely beyond parental control. And call me an egotist if you wish, but I do believe that my wife and I are able to make good enough choices to keep my kid from being the top-ranked Al Qaeda recruit of 2027. (I’d say he should try for Princeton first.)

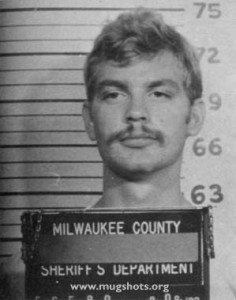

The best viewpoint I’ve ever read on this subject is that of Lionel Dahmer, father of Jeffrey Dahmer, the guy who (you may remember) was that nice fellow in Wisconsin, that one who always kept his lawn neat, and turned out to have an apartment full of decomposing corpses and a closet full of skulls. “A Father’s Story,” published a few years after the son’s arrest, imprisonment, and violent death at the hands of another inmate, is a memoir less of mea culpa than of bafflement. The elder Dahmer admits to being an imperfect parent, sometimes a distant one, sometimes an ineffective one. But clearly he did not do anything that actively produced a monster. This father’s autobiography is simply mournful, and conveys that he’d probably have turned his boy in himself–but that his own human frailty stopped him from seeing what he didn’t want to see. That, to me, is the saddest thought of all: Knowing deep down that your troubled kid is washing out to sea, and being emotionally unable, or unavailable, to help.