Two years ago, on the coldest day of the year, at 4:30 a.m., I could be found standing in line in the dark in Brooklyn, shivering, too cold even to drink coffee. J.P. was 2, and it was time to enroll him in a local preschool/daycare. Now, to say “enroll” makes the process seem in some way rational and humane. It wasn’t.

Consider the fact that I wasn’t even the first person on line at this ridiculous hour. I was second. There was a nice older lady who had arrived earlier than I had, which meant she was that much closer to freezing to death than me. She was not, however, the parent of a prospective student. She was a nanny. The family she worked for was on vacation in the Caribbean, and they had paid her $500 to be the first in line. This is what we in NYC call being smarter than you.

J.P. had been rejected by two other schools already, after paying an admission fee ($50 bucks, non-refundable), filling out the application (“describe your child’s strengths/weaknesses”) a group play with other kids working their way towards Harvard, and a visit to the home. This school, our last chance for the year, had no formal admission process — it was first come, first served. Doors open at 8 a.m., parents must arrive with check in hand, and the late ones can find a nanny, thank you very much.

By the time 8 a.m. rolled around, my decision to come so early seemed semi-sane. The line for admission stretched down the block and out of sight. If I had showed at 6:15, say, I would still have been freezing, but I also would have been shit out of luck.

This wonderful experience was but the first of the many awful hoops that parents in New York must jump through to educate their little ones. It starts with preschool and extends through elementary, high school, college, and into the cutthroat business of securing Junior’s Social Security benefits.

For those of you in Des Moines or wherever, places where the right school for your child means choosing between the local public and the local public, perhaps you might watch the trailer for “Nursery University,” to get an idea of what I’m talking about. Not convinced that it’s so bad? Well, do any of you out in suburbia have to hire an educational consultant to get your kid into nursery school?

Do you need an “action plan” that comes complete with school “information, procedures, maps, and data sheets”? What, you may ask, is a “data sheet” for a nursery school? Who knows? And is it really necessary to attend a “Intro to Nursery School lecture,” where for $20 you can hear (from someone who admits that her primary qualification as a consultant is the fact that she has twins) about “nursery school philosophy” and how to stay “under control and in perspective”?

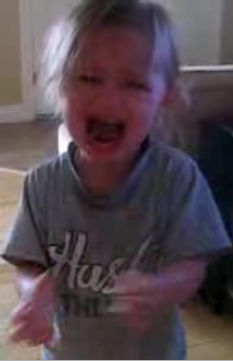

Do I seem under control and in perspective?

If this sounds like I’m complaining, I am. If you register a note of self-pity, rest assured that it’s there. If you think I haven’t called this woman already and asked for a discount…