A child’s development is a strange, lurching thing. You are convinced you kid can’t (or in some cases can) do this-or-that, and then on a dime, it all changes.

A child’s development is a strange, lurching thing. You are convinced you kid can’t (or in some cases can) do this-or-that, and then on a dime, it all changes.

This is how it went on Friday with my daughter.

The skill: water-survival.

The backstory: for years now our daughter, an intense and thoughtful five-year-old who is also prone to moments of deep physical cowardice, has had a conflicted relationship with pools. She loves them, of course: what child doesn’t? But she hates the anarchy of water, how it gets in your nose and mattes your hair, how it threatens to swallow you up whole at any moment. Her solution, improvised in a child’s manner, has been to gird herself with a mountain of gear and even more false bravado.

As in: here she is, with little pink flippers, a mask and snorkel, and a Coast Guard rated child’s lifejacket cinched tight around her chest, taking small steps into a bathwarm pool, careful not to wet her hair. She steps into open water, grasps onto a little inflatable boat for a moment then comes back to the steps, saying: “see, I told you I’m a good swimmer!”

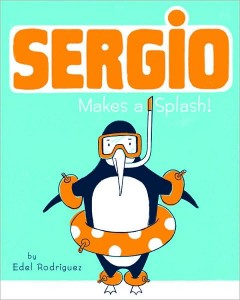

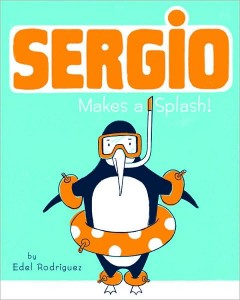

(For a rather exact portrait of her in the water, see Sergio Makes a Splash, a brilliant picture-book from my former colleague Edel Rodriguez, about a penguin who is not afraid of all water, just “the very deep kind.”)

My wife and I, ever helpful and encouraging in the style of parents who tell their children they did a great job when they crap in a toilet, applaud her accomplishment and tell her, when she returns to the step, that she’s a very good swimmer indeed.

Except, of course, that she isn’t. But it was only when my sister-in-law, a Miamian who would know about such things, pointed out that overconfidence can be a dangerous thing around the water, that we realized we were maybe doing our daughter a disservice by agreeing that she was a good swimmer. Maybe she realized that she actually wasn’t and was just saying so to seem brave or good. But more likely, we thought, she really thought that she was the kind of swimmer who could, say, jump off a boat or go into the pool with not adults around, and make it back to shore.

So on Friday morning, our second-to-last day of vacation in Key West, where I’m from, my wife set about to crush her little delusions like a grape. “You know, you can’t really swim,” my wife started, as Dalia once again boasted in the pool. “You have a life jacket and a little rubber boat, and that’s not swimming.”

Our daughter protested, but the mother was just getting warm.

“It’s important for you to know that you really can’t swim, because we don’t want you thinking you can be in the pool by yourself.”

And then my wife did something that proved unexpectedly clever. She spelled out what swimming really is: using your arms and legs to move through the water, without a lifejacket or rubber duckie or floatboard or anything like that.

We thought this would all defeat our daughter, make her cry a little, but help save her in the long run.

Instead, she took it as long-awaited instructions. She stood on the step, unbuckled her lifejacket, pushed into the pool, and swam.

As in, really swam. Feet behind her, arms working, body planked: she just swam. Straight across the pool.

And as she reached the far side, she picked up her head and asked, “like that?” without any trace of bravado or challenge, just a curiosity about whether that was indeed swimming.

For the next twenty minutes, she swam on her own. She joked around by floating still or frog-paddling. She didn’t panic or yelp or flail her arms like she had in the past. It was astounding.

So there you have it: one brief tiger-flash of cruel truth unlocked some internal ability that none of us–including her–thought she had. So my resolution for today: remind her that she can’t read and point out that her Spanish is crap. Then tonight we’ll be reading Cervantes in the original.

Okay, this isn’t so much a post as it is a miniature contest. Or a cry for help. Make that a scream from the pit of my stomach. Basically, I need your help, you brilliant DadWagon readers, to name a phenomenon.

Okay, this isn’t so much a post as it is a miniature contest. Or a cry for help. Make that a scream from the pit of my stomach. Basically, I need your help, you brilliant DadWagon readers, to name a phenomenon.